LSA Agent of Change Spotlight: Bethany Dengler-Germain We’re excited to announce that June’s “LSA Agent…

Q&A with Steve Kohlmann, PhD, CWB

Learn more about Carbon Sequestration efforts in rangelands and urban environments while benefiting disadvantaged communities and promoting equitable growth – a pioneering effort by Steve Kohlmann, an Associate/Senior Wildlife Biologist from LSA’s Point Richmond office.

What is your expertise with Carbon Sequestration and what makes it unique?

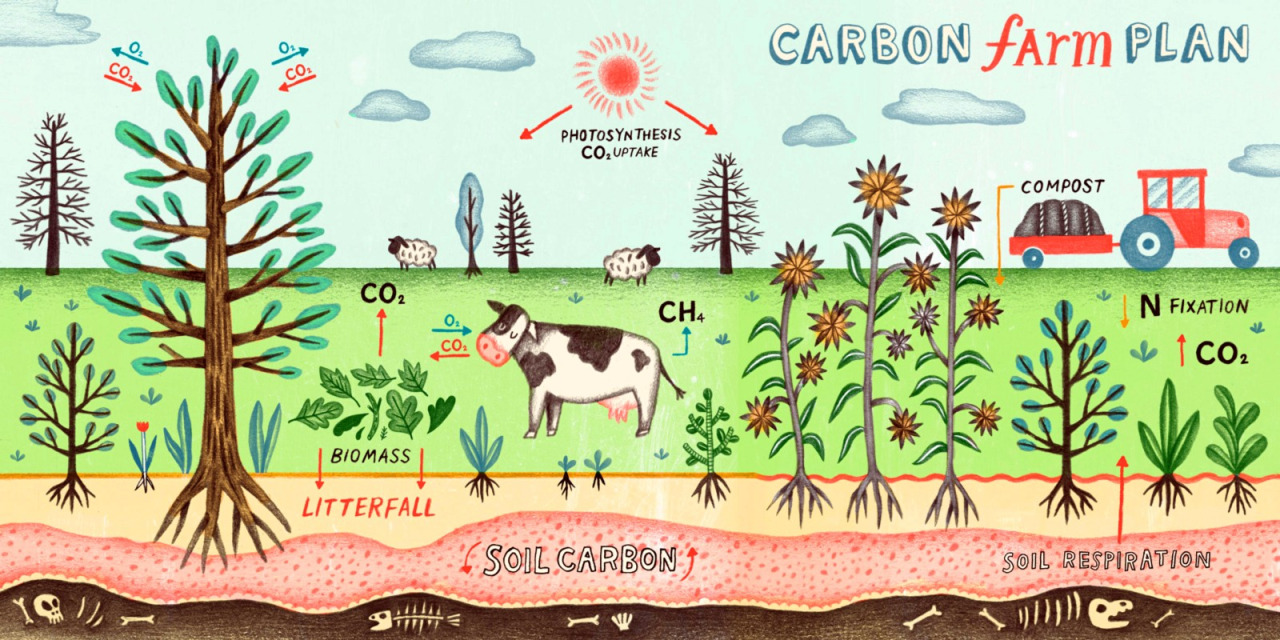

My interest in rangeland and forest carbon management started in graduate school. One of the most exciting trends in these disciplines is the increasing focus of sequestering (binding) carbon from the air into soil and biomass. This can offset carbon emissions from fossil fuel use because carbon tied up in the soil is removed from the atmosphere’s CO2 pool. Rangelands have a huge potential to store carbon permanently in the soil, due to the interaction of soil particles (clay), fungi, and microbial activity. It’s a fascinating world! Plants are incredibly efficient in capturing carbon (CO2) from the air, but to make the carbon stay in the soil we – as managers – need to ensure that vegetation communities are optimally managed to trap the carbon in the soil. Much of this type of management relies on native species, such as perennials, and a more diverse ecosystem where plants, fungi, and microbes form complex interactive systems. For farm soils, this often means no-till, cover crops, and multispecies cropping systems. Correct grazing and/or addition of natural soil amendments (such as compost or biochar) can profoundly alter rangeland soils to become a carbon “sink” (storage) that also is resilient to climate change, has high biodiversity, and produces food and fiber sustainably.

But carbon sequestration is not limited to just rangeland and forests. More and more we’re seeing neighborhoods, cities, and towns moving towards biological sequestration to offset carbon emissions. The primary way to do that in the urban environment is by expanding parks, urban greening and forestry, bioswales and infiltration strips to capture and infiltrate rainwater revegetation, and urban farms and community gardens. Individual homeowners can also sequester carbon by replacing lawns with carbon-beneficial vegetation, such as shrubs and perennials. The list of possibilities is endless! The concept of ecosystem services provided by these greenspaces to the humans living nearby is very useful in addressing the values of urban carbon sinks for public health, water and air quality, and biodiversity. I’m most excited about bringing carbon projects to disadvantaged communities, because they have such a potential to create equity and social justice benefits through open space, urban shading and cooling, local food production and educational opportunities (e.g., school gardens).

What are some models used?

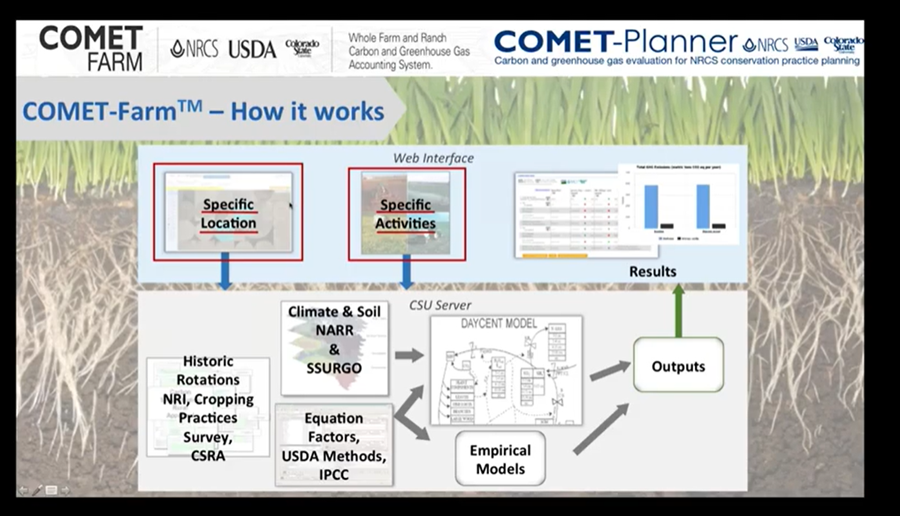

The past 20 years have brought on an incredible diversity of accounting tools for carbon in various landscapes. For farm and rangeland systems, the CometFarmPlanner is one of the most useful tools to estimate what amount of carbon can be sequestered when implementing some of the new techniques on farms and ranches. But we also have estimating models for riparian forests, wetlands, and grasslands. Carbon protocols are used almost exclusively to predict how much carbon storage would result from a given action. Currently, many of these protocols are used for Cap-and-Trade transactions, or for accreditation of carbon credits in the voluntary market. The accuracy of these models has been supported by many studies, keeping carbon projects accountable and realistic. For urban environments, a different set of models exists that predominantly track carbon storage by trees.

What are some key factors in providing these services?

Carbon projects must have realistic expectations. At the heart of each project are appropriate management techniques (what can actually be done in a sustainable way) and a team of managers that are capable and willing to conduct the necessary monitoring and management. For rangeland projects, it is important to find a producer that knows how carbon is accumulated in the soil, and who can manage grazing and grasslands in a way that is conducive to sequestration permanence (i.e., the sequestered carbon stays in the ground). When considering urban projects, it is paramount to include a wide range of stakeholders in the planning process. The co-benefits of carbon projects can be huge, especially for disadvantaged communities, where greenspace, air pollution, and urban heat islands are major problems. Ensuring a wide variety of participants from within the affected neighborhood not only tailors each project to the local needs, but more importantly engages stakeholders so that the project is supported in the future.

What do you like about this service/skill?

The opportunity to sequester carbon across landscapes and improve biodiversity and ecological functioning in rangelands is an exciting area to focus on. I love the concept of “working lands,” where producers, conservation organizations, and policy makers interface and work together to achieve climate goals. Working in urban environments has its challenges. As wildlife biologists, we tend to get excited about the wild places, or rare species. Urban environments in comparison are not very rich in biodiversity or  species. However, it is the notion of “keeping common species common” that excites me. In addition, being a dad of two kids, I feel we have an obligation towards the next generation to create livable communities, where kids can grow up in safety and health. Urban greenspaces fill so many diverse roles, but ultimately, they are habitat for humans. They provide “ecosystem services” that cannot be replicated by technology. In view of the impending climate crisis, I feel that urban greening is the primary tool for mitigating carbon, pollution, water, and wildlife impacts. And it provides the future generations with environmental equity and health benefits.

species. However, it is the notion of “keeping common species common” that excites me. In addition, being a dad of two kids, I feel we have an obligation towards the next generation to create livable communities, where kids can grow up in safety and health. Urban greenspaces fill so many diverse roles, but ultimately, they are habitat for humans. They provide “ecosystem services” that cannot be replicated by technology. In view of the impending climate crisis, I feel that urban greening is the primary tool for mitigating carbon, pollution, water, and wildlife impacts. And it provides the future generations with environmental equity and health benefits.

Why is this service area needed in California?

California has dense population centers, which are already feeling the brunt of the climate crisis. We are also one of the most prolific emitters of greenhouse gases in the nation. We have a great responsibility and opportunity to work for disadvantaged communities and help clean up our air and water and increase the livability of neighborhoods.

Are there any recent projects that you have worked on that demonstrate LSA’s ability to provide carbon sequestration expertise?

We recently completed an “ecosystem services assessment” for a former golf course in the Central Valley that is going to be a public park. Aside from carbon sequestration through trees, which amounted to the equivalent of about 400 cars per year, the park is located in a disadvantaged community and will provide access to nature and recreation to over 4,000 kids that had no greenspace to play in before. The park’s new purpose will also support some of the area’s endangered species and provide important fire and flood protection services.

Are there any fun facts you would like to share about your expertise?

We actually consider the methane from cattle burps as a greenhouse gas emission that reduces the carbon sequestration benefit of conservation grazing.